Murderer? The Story of James B. Shane

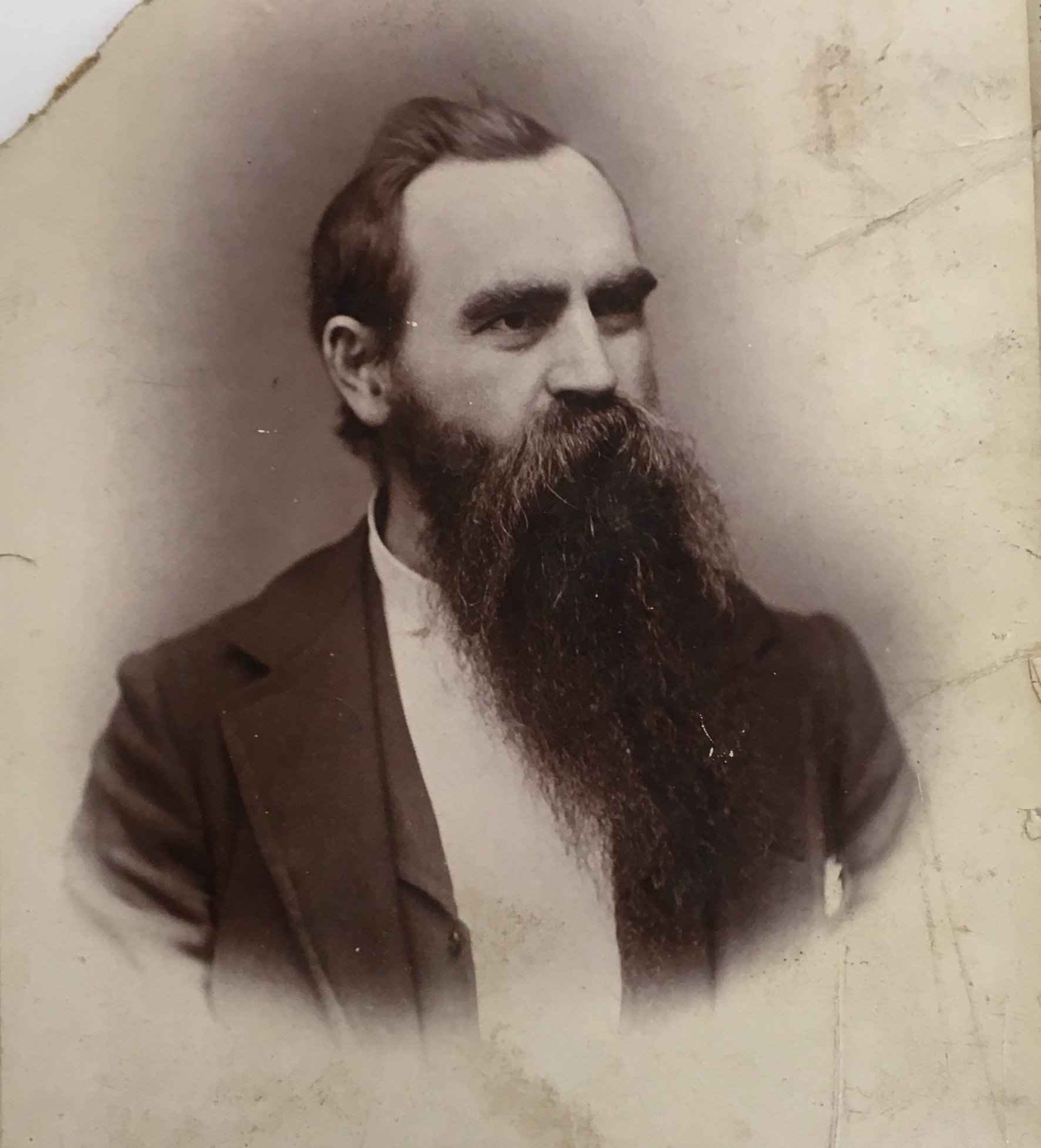

Born in Dover, Mason County, Kentucky on December 5th, 1840 to parents Nicholas and Statira Shane, James B. Shane has not only an interesting Civil War story, but also one involving murder after the war.

By 1860 the Shanes were living in Bracken County, the family occupied in maintaining their farm. Eight children, ranging in age from five to twenty-one, all supported the farm in various capacities. James Boucher Shanwas the second eldest child.

When the Civil War started in April 1861, eldest son John became a member of the 1st Kentucky Infantry, a unit filled with men mostly from Cincinnati. As Kentucky had declared itself neutral, and Ohio’s quota of men had been rapidly filled, the way to organize more Ohio men into service was to create the 1st and 2nd Kentucky Infantry Regiments. John enlisted as a private on May 23, 1861 at Camp Clay, and was mustered into service the following month. He would be promoted to first sergeant on March 28, 1864, and muster out of the 1st in June of that same year. John would then join the 54th Kentucky Infantry in September as a first lieutenant, and ending his Civil War service a year later.

Younger brother Richard was a private in Company D of the 16th Kentucky Infantry, serving his three year term and re-enlisting as a veteran volunteer. He had risen to the rank of corporal, and would be killed at Utoy Creek, Georgia on August 6, 1864.

Yet another younger brother, Charles, would join his eldest brother John in the 54th Kentucky Infantry in 1864. Seemingly as the Shane sons grew older they were able to go off to war as younger sons still at home could help on the farm.

James did not join the service until February 19, 1863 when he enlisted at Munfordville, Kentucky as a sergeant, joining brother Richard in Company D. James would be promoted to second lieutenant on the same day he enlisted, and would return home to marry Missouri Lee Quinlan in her father’s home in Brooksville on March 13, 1864 (presided over by Reverend Charles Heaverin and attended by Company D’s Captain Theodore C. Bratton). Returning to his regiment, James would see action throughout the Atlanta Campaign and at Utoy Creek would be severely wounded, causing his left leg to be amputated. However, this did not end James’s service as he would reenlist in May 1865, having risen to first lieutenant and would stay with the regiment until July. It is unclear how James was able to continue in the regiment with a missing leg unless he was on detached service. If he was with the regiment, he would have seen heavy fighting at Franklin, Tennessee on November 30, 1864 (the topic for an upcoming post).

After the war James and Missouri would move to Abilene, Kansas. James had wanted to become a lawyer, but the war had impacted his hearing and after trying several occupations he settled on becoming a photographer in Lawrence, having moved there in 1878. His photo studio was a railroad car (pictured above). Missouri was also involved in the photography profession, and at one time she and James both operated their own studios in Lawrence, just four blocks apart on Massachusetts Street, no longer using the railroad car. James was not a successful business man, and was known locally as an eccentric. With his failures and poor hearing, he became the target of sport, with young boys harrassing him, scrawling graffiti and throwing rocks and sticks into his studio. There are two stories on how Shane reacted.

The first tale is that one day the boys were throwing sticks into the studio and Shane reacted by pulling out a pistol and fatally shooting one of the the boys. The second story has more details: one day in 1902 Shane was closing up his shop to walk to his wife’s studio. As he exited the shop two boys were passing by, and Shane, eccentric, hard of hearing, and also known to have a bad temper, heard the boys say something that he took offense to. Like the first story, he had a pistol in his pocket and drew it out, intending to fire into to the air to scare the boys, but during his act his arm caught on a pole, the pistol fired, and one of the boys was killed.

Shane would be sentenced for murder. However, this is not the end of the story. In 1903 Shane would write (presumably from prison) Not Guilty, The Story of a Life (If anyone has a copy please contact us). By 1911 the Kansas Department of the Grand Army of the Republic had passed a resolution to appeal to the Kansas governor to get Shane out of jail. The appeal was based on the fact that Shane was not allowed to testify on his own behalf during his trial. If he had been allowed to testify, the appeal claims that the charges against Shane would have been reduced to manslaughter, a shorter prison term than murder. The ten children of James and Missouri also appeal to the governor, so after serving ten years of the murder conviction, James is set free. He is ill, and will die on December 28, 1913 at the age of seventy-three. Missouri had died in 1906 while her husband was in prison. One of their daughters would take over the business until her death in 1953. James and Missouri Shane are both buried in Lawrence’s Oak Hill Cemetery.